The recent TD Bank money laundering case highlights the stark hypocrisy and double standards in the financial system’s enforcement of anti-money laundering (AML) and know-your-customer (KYC) policies. Despite facilitating over $670 million in laundered funds and failing to monitor $18.3 trillion in customer transactions, TD Bank and its executives face minimal consequences, paying a symbolic fine while continuing business as usual. In contrast, developers of decentralized, privacy-focused tools like Samourai Wallet and Tornado Cash are being prosecuted for merely creating noncustodial applications that could possibly be misused by bad actors, despite having no control over their use. This selective enforcement reveals how legacy financial institutions are protected while open-source developers are harshly targeted, exposing a systemic bias against decentralized innovation, and freedom-enhancing technologies.

How Can This Even Happen With a “Regulated” Financial Entity?

The TD Bank money laundering case is a glaring example of the double standards that permeate the global financial system, particularly in how regulatory authorities enforce laws for legacy financial institutions versus decentralized technologies. Despite the strict implementation of anti-money laundering (AML) and know-your-customer (KYC) policies, TD Bank, one of the largest financial institutions in North America, admitted to systemic failures that allowed over $670 million to be laundered through its accounts over the course of nearly a decade. The bank’s failure to monitor $18.3 trillion in customer transactions over this period reflects a deep flaw in the regulatory frameworks that were designed to prevent such occurrences. Instead of facing severe consequences like crypto app developers, TD Bank executives will pay a hefty, yet symbolic, fine of $3 billion, a mere fraction of the bank’s revenue, and continue operating largely unimpeded.

This case underscores the ineffectiveness of financial surveillance policies like AML and KYC, which are frequently touted as necessary safeguards against criminal activity. On top of AML/KYC being totally ineffective, these systems have become prime targets for cybercrime, with the constant breaches of sensitive personal information and customer data demonstrating how impossibly hard it is to secure such vast troves of private data. Ironically, these policies are applied rigorously to smaller players and decentralized entities creating extremely costly and prohibitive regulatory burdens, while allowing major banks like TD Bank to operate with minimal oversight, even when they are caught red-handed, facilitating significant financial crimes. The fact that TD Bank not only allowed money laundering but also had employees directly involved in the schemes, taking bribes to facilitate illicit transactions, illustrates how ineffective these policies are when the institution itself is complicit. These employees processed suspicious cash deposits and created shell companies, directly enabling drug cartels and other criminal networks to move their funds.

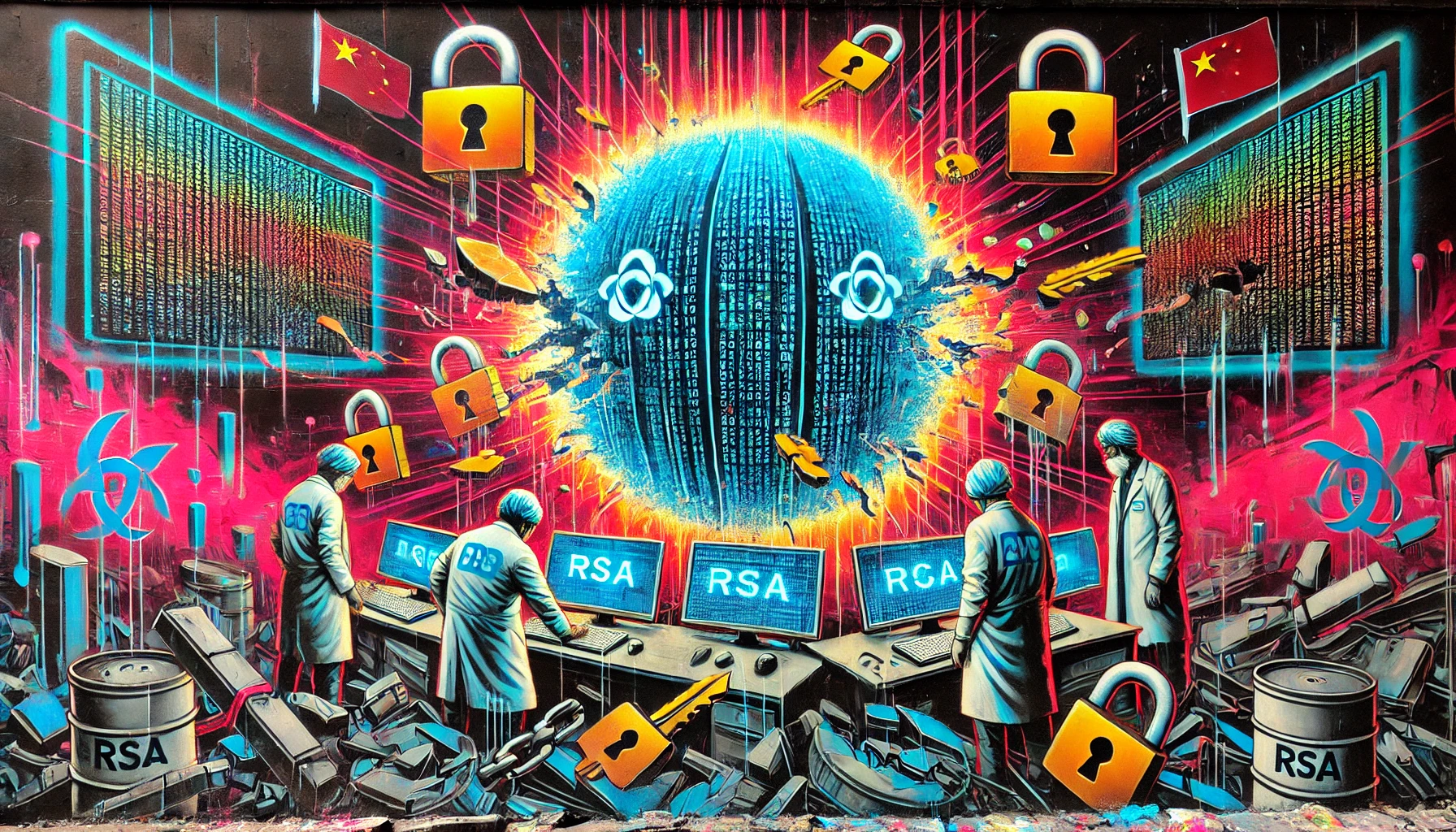

Meanwhile, decentralized financial systems, including developers of privacy-focused tools like Samourai Wallet and Tornado Cash, face a very different kind of scrutiny. Developers of these noncustodial platforms have been charged with serious crimes such as money laundering and operating unlicensed money transmission services, even though they merely provided tools that protect user privacy. These open-source developers are now at risk of facing lengthy prison sentences for writing code that, while aimed at enhancing financial privacy, may possibly be used by bad actors in ways outside of the developers’ control or intent. Unlike traditional financial institutions, which often evade meaningful punishment, these developers are being held to a much higher standard, despite the fact that their platforms do not facilitate transactions themselves or profit from illicit activities.

The hypocrisy is stark. Traditional financial institutions like TD Bank, whose business model is deeply intertwined with the global financial system, can engage in money laundering on an institutional scale with few personal repercussions for their executives. They can settle cases with fines, retain profits, and make vague promises to improve their compliance programs, steps that are often seen as little more than PR damage control. In contrast, decentralized platforms face existential threats for creating tools that prioritize user autonomy and privacy. Tornado Cash, for example, is a decentralized application that allows users to obfuscate the source of their Ethereum transactions, bringing otherwise fully transparent blockchain transactions up to a level of privacy on par with a traditional bank account. While the developers had no direct involvement in the criminal activities that used the platform, they are being prosecuted as if they orchestrated these illegal acts themselves.

This selective enforcement of financial laws reveals an alarming double standard. On one hand, banks like TD are fined a sum that is essentially a cost of doing business, without any meaningful changes to their operations or holding their executives personally accountable, who will never ever face serious jail time. On the other hand, open-source developers face life-altering consequences for creating privacy-preserving software that could be misused by a small fraction of their user base. The message being sent is clear: financial crimes committed by institutions that are deeply embedded in the traditional financial system are tolerable, while those providing tools that allow individuals to protect their privacy from surveillance are treated as threats to the system itself.

The broader implication of this selective enforcement is the chilling effect it has on innovation in the DeFi or cryptocurrency space. Developers are being forced to weigh the risk of legal action simply for providing privacy-enhancing tools, which are essential in a world where financial surveillance is increasingly pervasive, surveillance capitalism is the preferred business model, and institutions increasingly use this data against the very people who create it in the first place. This contrast, between legacy financial institutions like TD Bank, who can launder money with minimal consequence, and developers of decentralized platforms who face the full brunt of the law for offering privacy solutions, illustrates a systemic bias. It shows that the global financial system is less concerned with preventing financial crimes and more focused on maintaining control over who can participate in the financial system. While banks can continue profiting from illicit activities, those working to build decentralized alternatives face unjust persecution.